You bring to the Education Program years of experience as a teacher and school leader in the Boston Public Schools. What inspired you to get into education?

I’ve told this story 100 different ways, but it always starts with my parents. My father was a music teacher, my mother became a school nurse when I was 10, and they both retired from the School District of Philadelphia. So, you could say that I fell into the family business in a way.

But it’s deeper than that. I’m a product of educational opportunity. I’m from a neighborhood in West Philadelphia called Mantua which was predominantly Black and lower income. In Philly, like many places in our country both then and now, your neighborhood determined where you went to school, and your neighborhood’s demographics determined functional access to opportunity. Not just who attended your school, but also the broader public narrative, perception, and belief held by some around needs, resources, and expected outcomes. Sitting two blocks from my house and across the street from a high-rise public housing development, my local K-8 school was a persistently “low-performing,” under-resourced school… that I never attended.

Because of my father’s social capital as an educator, my parents received support navigating the paper-based school transfer process, a vestige of Philadelphia’s attempts to racially integrate schools. Through this, I had the opportunity to attend the school where my father worked, eight blocks away — just one neighborhood over. But, unlike my local school, it was racially and socioeconomically diverse. It had been founded in the late 60s, during the progressive educational movement as an intentionally desegregated school and in Philadelphia it was a gateway to opportunity.

I got that opportunity. It wasn’t offered to every young person who grew up in my neighborhood, and I’m just not OK with that. I don’t believe we can deliver on the ideals of a democratic society without ensuring that all students have access to the kind of learning experiences I gained access to. Every student deserves that.

I became a teacher because I felt like I had an obligation to take what I had received and give it back, particularly to students who grew up in neighborhoods like mine, with backgrounds like mine.

I started as a secondary math teacher and eventually felt the encouragement and pull to consider more systemic challenges. That took me to graduate school, leadership positions at the Boston Public Schools, and now here. But no matter what seat I’m in, my focus has been on making schools and our schooling system increasingly equitable and excellent, giving particular attention to the communities and students our society continues to serve poorly.

How does that experience inform your approach to grantmaking?

My experience has informed my entire career and some key beliefs that will undoubtedly inform my grantmaking in evolving ways. I’ve approached my career with the belief that all students are worthy of educational opportunities like I received. I believe the bar for achieving this kind of equity and excellence is very high, likely higher than the field of education and our broader society has acknowledged. Despite this high challenge, I sense a growing desire from the field to aspire to reach it.I don’t believe our systems have figured out how to do it yet and this honestly fills me with hope, because it means that our future could be fundamentally different from the past that our society has inherited.

Having spent the majority of my career in schools – and being the proud son to educators – I sense how much is being asked and demanded of teachers and leaders to reach this aspiration and how much the support they are given to succeed is falling short. I believe that transforming our education system requires focusing on the “instructional core,” as Richard Elmore put it — the intersection of teachers, students, and content. What happens at the core matters most and everything else around it should be in service of protecting, deepening, and strengthening the quality of interactions between teachers, students, and content.

As I lead the Invest in Educators portfolio, I’m constantly thinking about how an individual grant or a body of grantmaking will impact who is leading in our classrooms, schools, and districts and how they are being prepared and developed in their work. I’m holding onto my lived experience as an educator tightly, keeping my focus there.

What does “investing in educators” mean to you?

Education is fundamentally a human endeavor and the people who do the work matter tremendously. Not just the identities they hold, the skills they develop, and the outcomes they achieve for students, but also how they are seen, valued, and supported along the way.

At times, I feel as though some of the initiatives within education reform are predicated on “human-proofing” education, treating the people who do the work as interchangeable parts in some kind of assembly line. I have so much respect for the profession and the people who choose to enter classrooms and teach, and who choose to enter schools to support and lead.

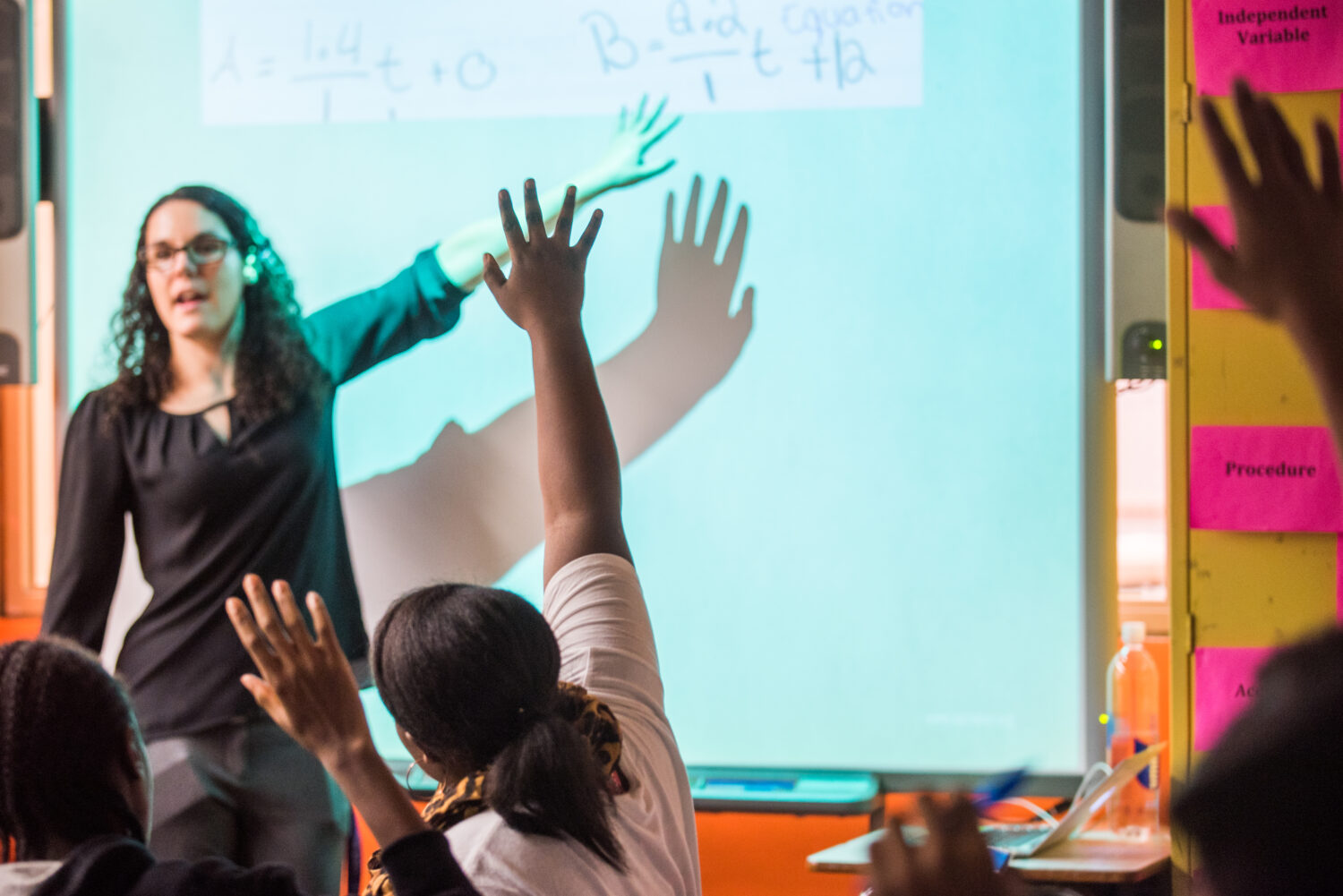

When I was in eighth grade, I was struggling so much in math that I became actively defiant toward learning. I wouldn’t open my notebook or complete my homework. I was confused and embarrassed and on my first report card earned the worst grade I had ever received. I was disengaging as a learner.

I thank the Lord every day that Michael Neights was my eighth-grade math teacher. Somehow, even though I had given up on math and on myself, he refused to give up on me. He helped me see that if I shifted my approach to learning, I could be successful. He was willing to stay late and talk with me, person to person. At the risk of hyperbole, he changed my life.

As a Black man from West Philadelphia, there were many other versions of my life story that could have been written. Mr. Neights took the extra step to know me, communicate unwavering belief in my potential, and write himself into my story. Years on, as an early career math teacher, I thought about him often.

Every classroom deserves a great teacher. Every school deserves a great leader. And I think our present ecosystem is not structured in a way to support the people who do the work to make that a reality everywhere.

Are there specific projects, grants, or initiatives you’re excited to work on at Barr?

It has been such a privilege to sit in this seat and meet all of our amazing grantee organizations and their leaders. The Invest in Educators portfolio supports organizations who support educators – teachers, principals, superintendents – both directly and indirectly. Two major efforts that I have been excited to inherit are our Strengthening School Leadership cohort and Driving Towards Diversity cohort of schools and districts. Through respected organizations like the Lynch Leadership Academy, Relay Graduate School of Education, School Empowerment Network, and TNTP (formerly the New Teacher Project), districts across these cohorts have been redesigning their approach to developing and supporting school leaders and examining their talent practices to increase the diversity of their educator workforce.

In light of the recent Supreme Court decision related to affirmative action, organizations like The Teachers’ Lounge—committed to cultivating communities where educators of color thrive, and He Is Me Institute—striving to see more black men enter teaching— have been particularly on my mind. These are the sorts of programs I wished existed when I started my own career. I am proud of the many organizations across the portfolio that refuse to allow a court to erase history and the lingering impacts of racist policies, practices, and beliefs.

So you got your start teaching mathematics. What’s your favorite thing about math?

After my eighth-grade teacher helped me turn things around in math, it officially became my favorite subject in high school. I found it fascinating, particularly calculus and statistics. The thing I love about mathematics, and the teaching of it, is that it is a rich context for learning that we can do more than we think we can. Many students think they can’t be successful at math until they work with someone who helps them believe in themselves. That was my story. I tried to be that type of educator for my students and school leader for my staff.

No matter what I am doing, whether I’m a teacher, a principal, or working in a district central office, I get really excited about helping people achieve things they didn’t think were possible. And my role at Barr is allowing me to keep doing that.